Havell Name

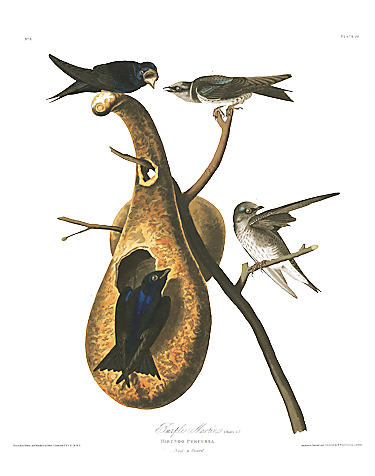

Purple Martin

Common Name

Purple Martin

Havell Plate No.

022

Paper Size

39″ x 28″

Image Size

21″ x 16″

Price

$ 1,200

Ornithological Biography

The Purple Martin makes its appearance in the City of New Orleans from the 1st to the 9th of February, occasionally a few days earlier than the first of these dates, and is then to be seen gambolling through the air, over the city and the river, feeding on many sorts of insects, which are there found in abundance at that period.

It frequently rears three broods whilst with us. I have had several opportunities, at the period of their arrival, of seeing prodigious flocks moving over that city or its vicinity, at a considerable height, each bird performing circular sweeps as it proceeded, for the purpose of procuring food. These flocks were loose, and moved either eastward, or towards the north-west, at a rate not exceeding four miles in the hour, as I walked under one of them with ease for upwards of two miles, at that rate, on the 4th of February, 1821, on the bank of the river below the city, constantly looking up at the birds, to the great astonishment of many passengers, who were bent on far different pursuits. My Fahrenheit’s thermometer stood at 68 degrees, the weather being calm and drizzly. This flock extended about a mile and a half in length, by a quarter of a mile in breadth. On the 9th of the same month, not far above the Battleground, I enjoyed another sight of the same kind, although I did not think the flock so numerous.

At the Falls of the Ohio, I have seen Martins as early as the 15th of March, arriving in small detached parties of only five or six individuals, when the thermometer was as low as 28 degrees, the next day at 45 degrees, and again, in the same week, so low as to cause the death of all the Martins, or to render them so incapable of flying as to suffer children to catch them. By the 25th of the same month, they are generally plentiful about that neighbourhood.

At St. Genevieve, in the State of Missouri, they seldom arrive before the 10th or 15th of April, and sometimes suffer from unexpected returns of frost. At Philadelphia, they are first seen about the 10th of April. They reach Boston about the 25th, and continue their migration much farther north, as the spring continues to open.

On their return to the Southern States, they do not require to wait for warmer days, as in spring, to enable them to proceed, and they all leave the above-mentioned districts and places about the 20th of August. They assemble in parties of from fifty to a hundred and fifty, about the spires of churches in the cities, or on the branches of some large dead tree about the farms, for several days before their final departure. From these places they are seen making occasional sorties, uttering a general cry, and inclining their course towards the west, flying swiftly for several hundred yards, when suddenly checking themselves in their career, they return in easy sailings to the same tree or steeple. They seem to act thus for the purpose of exercising themselves, as well as to ascertain the course they are to take, and to form the necessary arrangements for enabling the party to encounter the fatigues of their long journey. Whilst alighted, during these days of preparation, they spend the greater part of the time in dressing and oiling their feathers, cleaning their skin, and clearing, as it were, every part of their dress and body from the numerous insects which infest them. They remain on their roosts exposed to the night air, a few only resorting to the boxes where they have been reared, and do not leave them until the sun has travelled an hour or two from the horizon, but continue, during the fore part of the morning to plume themselves with great assiduity. At length, on the dawn of a calm morning, they start with one accord, and are seen moving due west or southwest, joining other parties as they proceed, until there is formed a flock similar to that which I have described above. Their progress is now much more rapid than in spring, and they keep closer together.

It is during these migrations, reader, that the power of flight possessed by these birds can be best ascertained, and more especially when they encounter a violent storm of wind. They meet the gust, and appear to slide along the edges of it, as if determined not to lose one inch of what they have gained. The foremost front the storm with pertinacity, ascending or plunging along the skirts of the opposing currents, and entering their undulating recesses, as if determined to force their way through, while the rest follow close behind, all huddled together into such compact masses as to appear like a black spot. Not a twitter is then to be heard from them by the spectator below; but the instant the farther edge of the current is doubled, they relax their efforts, to refresh themselves, and twitter in united accord, as if congratulating each other on the successful issue of the contest.

The usual flight of this bird more resembles that of the Hirundo urbica of LINNAEUS, or that of the Hirundo fulva of VIEILLOT, than the flight of any other species of Swallow; and, although graceful and easy, cannot be compared in swiftness with that of the Barn Swallow. Yet the Martin is fully able to distance any bird not of its own genus. They are very expert at bathing and drinking while on the wing, when over a large lake or river, giving a sudden motion to the hind part of the body, as it comes into contact with the water, thus dipping themselves in it, and then rising and shaking their body, like a water spaniel, to throw off the water. When intending to drink, they sail close over the water, with both wings greatly raised, and forming a very acute angle with each other. In this position, they lower the head, dipping their bill several times in quick succession, and swallowing at each time a little water.

They alight with comparative ease on different trees, particularly willows, making frequent movements of the wings and tail as they shift their place, in looking for leaves to convey to their nests. They also frequently alight on the ground, where, notwithstanding the shortness of their legs, they move with some ease, pick up a goldsmith or other insect, and walk to the edges of puddles to drink, opening their wings, which they also do when on trees, feeling as if not perfectly comfortable.

These birds are extremely courageous, persevering, and tenacious of what they consider their right. They exhibit strong antipathies against cats, dogs, and such other quadrupeds as are likely to prove dangerous to them. They attack and chase indiscriminately every species of Hawk, Crow, or Vulture, and on this account are much patronized by the husbandman. They frequently follow and tease an Eagle, until he is out of sight of the Martin’s box; and to give you an idea of their tenacity, when they have made choice of a place in which to rear their young, I shall relate to you the following occurrences.

It frequently rears three broods whilst with us. I have had several opportunities, at the period of their arrival, of seeing prodigious flocks moving over that city or its vicinity, at a considerable height, each bird performing circular sweeps as it proceeded, for the purpose of procuring food. These flocks were loose, and moved either eastward, or towards the north-west, at a rate not exceeding four miles in the hour, as I walked under one of them with ease for upwards of two miles, at that rate, on the 4th of February, 1821, on the bank of the river below the city, constantly looking up at the birds, to the great astonishment of many passengers, who were bent on far different pursuits. My Fahrenheit’s thermometer stood at 68 degrees, the weather being calm and drizzly. This flock extended about a mile and a half in length, by a quarter of a mile in breadth. On the 9th of the same month, not far above the Battleground, I enjoyed another sight of the same kind, although I did not think the flock so numerous.

At the Falls of the Ohio, I have seen Martins as early as the 15th of March, arriving in small detached parties of only five or six individuals, when the thermometer was as low as 28 degrees, the next day at 45 degrees, and again, in the same week, so low as to cause the death of all the Martins, or to render them so incapable of flying as to suffer children to catch them. By the 25th of the same month, they are generally plentiful about that neighbourhood.

At St. Genevieve, in the State of Missouri, they seldom arrive before the 10th or 15th of April, and sometimes suffer from unexpected returns of frost. At Philadelphia, they are first seen about the 10th of April. They reach Boston about the 25th, and continue their migration much farther north, as the spring continues to open.

On their return to the Southern States, they do not require to wait for warmer days, as in spring, to enable them to proceed, and they all leave the above-mentioned districts and places about the 20th of August. They assemble in parties of from fifty to a hundred and fifty, about the spires of churches in the cities, or on the branches of some large dead tree about the farms, for several days before their final departure. From these places they are seen making occasional sorties, uttering a general cry, and inclining their course towards the west, flying swiftly for several hundred yards, when suddenly checking themselves in their career, they return in easy sailings to the same tree or steeple. They seem to act thus for the purpose of exercising themselves, as well as to ascertain the course they are to take, and to form the necessary arrangements for enabling the party to encounter the fatigues of their long journey. Whilst alighted, during these days of preparation, they spend the greater part of the time in dressing and oiling their feathers, cleaning their skin, and clearing, as it were, every part of their dress and body from the numerous insects which infest them. They remain on their roosts exposed to the night air, a few only resorting to the boxes where they have been reared, and do not leave them until the sun has travelled an hour or two from the horizon, but continue, during the fore part of the morning to plume themselves with great assiduity. At length, on the dawn of a calm morning, they start with one accord, and are seen moving due west or southwest, joining other parties as they proceed, until there is formed a flock similar to that which I have described above. Their progress is now much more rapid than in spring, and they keep closer together.

It is during these migrations, reader, that the power of flight possessed by these birds can be best ascertained, and more especially when they encounter a violent storm of wind. They meet the gust, and appear to slide along the edges of it, as if determined not to lose one inch of what they have gained. The foremost front the storm with pertinacity, ascending or plunging along the skirts of the opposing currents, and entering their undulating recesses, as if determined to force their way through, while the rest follow close behind, all huddled together into such compact masses as to appear like a black spot. Not a twitter is then to be heard from them by the spectator below; but the instant the farther edge of the current is doubled, they relax their efforts, to refresh themselves, and twitter in united accord, as if congratulating each other on the successful issue of the contest.

The usual flight of this bird more resembles that of the Hirundo urbica of LINNAEUS, or that of the Hirundo fulva of VIEILLOT, than the flight of any other species of Swallow; and, although graceful and easy, cannot be compared in swiftness with that of the Barn Swallow. Yet the Martin is fully able to distance any bird not of its own genus. They are very expert at bathing and drinking while on the wing, when over a large lake or river, giving a sudden motion to the hind part of the body, as it comes into contact with the water, thus dipping themselves in it, and then rising and shaking their body, like a water spaniel, to throw off the water. When intending to drink, they sail close over the water, with both wings greatly raised, and forming a very acute angle with each other. In this position, they lower the head, dipping their bill several times in quick succession, and swallowing at each time a little water.

They alight with comparative ease on different trees, particularly willows, making frequent movements of the wings and tail as they shift their place, in looking for leaves to convey to their nests. They also frequently alight on the ground, where, notwithstanding the shortness of their legs, they move with some ease, pick up a goldsmith or other insect, and walk to the edges of puddles to drink, opening their wings, which they also do when on trees, feeling as if not perfectly comfortable.

These birds are extremely courageous, persevering, and tenacious of what they consider their right. They exhibit strong antipathies against cats, dogs, and such other quadrupeds as are likely to prove dangerous to them. They attack and chase indiscriminately every species of Hawk, Crow, or Vulture, and on this account are much patronized by the husbandman. They frequently follow and tease an Eagle, until he is out of sight of the Martin’s box; and to give you an idea of their tenacity, when they have made choice of a place in which to rear their young, I shall relate to you the following occurrences.

I had a large and commodious box built and fixed on a pole, for the reception of Martins, in an enclosure near my house, where for some years several pairs had reared their young. One winter I also put up several small boxes, with a view to invite Blue-birds to build nests in them. The Martins arrived in the spring, and imagining these smaller apartments more agreeable than their own mansion, took possession of them, after forcing the lovely Blue-birds from their abode. I witnessed the different conflicts, and observed that one of the Blue-birds was possessed of as much courage as his antagonist, for it was only in consequence of the more powerful blows of the Martin, that he gave up his house, in which a nest was nearly finished, and he continued on all occasions to annoy the usurper as much as lay in his power. The Martin shewed his head at the entrance, and merely retorted with accents of exultation and insult. I thought fit to interfere, mounted the tree on the trunk of which the Blue-bird’s box was fastened, caught the Martin, and clipped his tail with scissors, in the hope that such mortifying punishment might prove effectual in inducing him to remove to his own tenement. No such thing; for no sooner had I launched him into the air, than he at once rushed back to the box. I again caught him, and clipped the tip of each wing in such a manner that he still could fly sufficiently well to procure food, and once more set him at liberty. The desired effect, however, was not produced, and as I saw the pertinacious Martin keep the box in spite of all my wishes that he should give it up, I seized him in anger, and disposed of him in such a way that he never retuned to the neighbourhood.

At the house of a friend of mine in Louisiana, some Martins took possession of sundry holes in the cornices, and there reared their young for several years, until the insects which they introduced to the house induced the owner to think of a reform. Carpenters were employed to clean the place, and close up the apertures by which the birds entered the cornice. This was soon done. The Martins seemed in despair; they brought twigs and other materials, and began to form nests wherever a hole could be found in any part of the building; but were so chased off that after repeated attempts, the season being in the mean time advanced, they were forced away, and betook themselves to some Woodpeckers’ holes on the dead trees about the plantation. The next spring, a house was built for them. The erection of such houses is a general practice, the Purple Martin being considered as a privileged pilgrim, and the harbinger of spring.

The note of the Martin is not melodious, but is nevertheless very pleasing. The twitterings of the male while courting the female are more interesting. Its notes are among the first that are heard in the morning, and are welcome to the sense of every body. The industrious farmer rises from his bed as he hears them. They are soon after mingled with those of many other birds, and the husbandman, certain of a fine day, renews his peaceful labours with an elated heart. The still more independent Indian is also fond of the Martin’s company. He frequently hangs up a calabash on some twig near his camp, and in this cradle the bird keeps watch, and sallies forth to drive off the Vulture that might otherwise commit depredations on the deer-skins or pieces of venison exposed to the air to be dried. The slaves in the Southern States take more pains to accommodate this favourite bird. The calabash is neatly scooped out, and attached to the flexible top of a cane, brought from the swamp, where that plant usually grows, and placed close to their huts. Almost every country tavern has a Martin box on the upper part of its sign-board; and I have observed that the handsomer the box, the better does the inn generally prove to be.

All our cities are furnished with houses for the reception of these birds; and it is seldom that even lads bent upon mischief disturb the favoured Martin. He sweeps along the streets, here and there seizing a fly, bangs to the eaves of the houses, or peeps into them, as he poises himself in the air in front of the windows, or mounts high above the city, soaring into the clear sky, plays with the string of the child’s kite, snapping at it, as he swiftly passes, with unerring precision, or suddenly sweeps along the roofs, chasing off grimalkin, who is probably prowling in quest of his young.

In the Middle States, the nest of the Martin is built, or that of the preceding year repaired and augmented, eight or ten days after its arrival, or about the 20th of April. It is composed of dry sticks, willow-twigs, grasses, leaves green and dry, feathers, and whatever rags he meets with. The eggs, which are pure white, are from four to six. Many pairs resort to the same box to breed, and the little fraternity appear to live in perfect harmony. They rear two broods in a season. The first comes forth in the end of May, the second about the middle of July. In Louisiana, they sometimes have three broods. The male takes part of the labour of incubation, and is extremely attentive to his mate. He is seen twittering on the box, and frequently flying past the hole. His notes are at this time emphatical and prolonged, low and less musical than even his common pews. Their food consists entirely of insects, among which are large beetles. They seldom seize the honey-bee.

The circumstance of their leaving the United States so early in autumn, has inclined me to think that they must go farther south than any of our migratory land birds.

At the house of a friend of mine in Louisiana, some Martins took possession of sundry holes in the cornices, and there reared their young for several years, until the insects which they introduced to the house induced the owner to think of a reform. Carpenters were employed to clean the place, and close up the apertures by which the birds entered the cornice. This was soon done. The Martins seemed in despair; they brought twigs and other materials, and began to form nests wherever a hole could be found in any part of the building; but were so chased off that after repeated attempts, the season being in the mean time advanced, they were forced away, and betook themselves to some Woodpeckers’ holes on the dead trees about the plantation. The next spring, a house was built for them. The erection of such houses is a general practice, the Purple Martin being considered as a privileged pilgrim, and the harbinger of spring.

The note of the Martin is not melodious, but is nevertheless very pleasing. The twitterings of the male while courting the female are more interesting. Its notes are among the first that are heard in the morning, and are welcome to the sense of every body. The industrious farmer rises from his bed as he hears them. They are soon after mingled with those of many other birds, and the husbandman, certain of a fine day, renews his peaceful labours with an elated heart. The still more independent Indian is also fond of the Martin’s company. He frequently hangs up a calabash on some twig near his camp, and in this cradle the bird keeps watch, and sallies forth to drive off the Vulture that might otherwise commit depredations on the deer-skins or pieces of venison exposed to the air to be dried. The slaves in the Southern States take more pains to accommodate this favourite bird. The calabash is neatly scooped out, and attached to the flexible top of a cane, brought from the swamp, where that plant usually grows, and placed close to their huts. Almost every country tavern has a Martin box on the upper part of its sign-board; and I have observed that the handsomer the box, the better does the inn generally prove to be.

All our cities are furnished with houses for the reception of these birds; and it is seldom that even lads bent upon mischief disturb the favoured Martin. He sweeps along the streets, here and there seizing a fly, bangs to the eaves of the houses, or peeps into them, as he poises himself in the air in front of the windows, or mounts high above the city, soaring into the clear sky, plays with the string of the child’s kite, snapping at it, as he swiftly passes, with unerring precision, or suddenly sweeps along the roofs, chasing off grimalkin, who is probably prowling in quest of his young.

In the Middle States, the nest of the Martin is built, or that of the preceding year repaired and augmented, eight or ten days after its arrival, or about the 20th of April. It is composed of dry sticks, willow-twigs, grasses, leaves green and dry, feathers, and whatever rags he meets with. The eggs, which are pure white, are from four to six. Many pairs resort to the same box to breed, and the little fraternity appear to live in perfect harmony. They rear two broods in a season. The first comes forth in the end of May, the second about the middle of July. In Louisiana, they sometimes have three broods. The male takes part of the labour of incubation, and is extremely attentive to his mate. He is seen twittering on the box, and frequently flying past the hole. His notes are at this time emphatical and prolonged, low and less musical than even his common pews. Their food consists entirely of insects, among which are large beetles. They seldom seize the honey-bee.

The circumstance of their leaving the United States so early in autumn, has inclined me to think that they must go farther south than any of our migratory land birds.